DET002 - The Detroit River: A Lifeline of History and Industry

- Patrick Foley

- Feb 11

- 4 min read

The Detroit River, a defining geographical feature of the city, has long played a crucial role in shaping its identity. A natural boundary between the United States and Canada, the river serves as a vital waterway, linking the Great Lakes to the Atlantic. Its importance rivals that of the Thames in London, the Seine in Paris, or the Hudson in New York. Unlike many rivers that become tainted by industrialization, the Detroit River has remained remarkably pure, with its waters retaining a clarity that early travelers marveled at. Its steady currents and navigability made it an essential artery for commerce, warfare, and settlement, fostering the growth of Detroit into a major metropolis.

Stretching approximately 27 miles from Windmill Point at Lake St. Clair to Bar Point at Lake Erie, the river varies in width from just over half a mile at its narrowest to three miles at its widest. The depth ranges from ten to sixty feet, with an average of thirty-four feet, making it navigable for even the largest vessels. Recognized as a public highway by the U.S. Congress in 1819, the river has carried more tonnage through Detroit than the Thames sees in London. It functions as a drainage channel for a vast expanse of land and lake surface, channeling the combined waters of Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, and St. Clair, along with numerous tributaries, into Lake Erie. The sheer volume of water moving through the river is staggering—over 212,000 cubic feet per second—making it one of the most significant freshwater conduits in the world.

The river’s tranquil nature has made it an inviting waterway for generations of boaters, traders, and settlers. Early accounts describe its surface as so still and reflective that the smoke from indigenous wigwams mirrored perfectly on the water. Canoes once lined its shores, while windmills dotted the landscape, their arms turning in the breeze, marking the presence of small European settlements. Later, the rise of industrialization transformed these shores into bustling ports with docks and wharves extending into the water, supporting an economy driven by manufacturing and trade.

Despite the river’s general calmness, it has experienced fluctuations in water levels over the centuries. Records from 1800, 1814-1815, 1827-1828, and 1838 note significant rises of up to six feet above normal, while particularly cold winters saw ice thick enough to support foot traffic and even temporary structures. The most notable freeze occurred in 1855 when the river was so solidly frozen that a small shanty was erected midstream to sell liquor to travelers. However, since 1854, the daily crossings of railroad ferry boats have prevented such complete freezes. Ice harvesting became a major industry, with between 50,000 and 100,000 tons of ice stored annually for use in the warmer months.

The Detroit River’s many islands further enhance its character and historical significance. These islands, numbering over twenty, have served various roles throughout history. Belle Isle, now the city’s beloved park, was once a secluded retreat. Fighting Island, once known as Great Turkey Island, bore witness to indigenous conflicts and later served as a settlement for the Wyandots. Grosse Isle, the largest island, was once considered as a potential site for the founding of Detroit itself, though concerns over timber shortages led settlers to establish the city on the mainland. Its lush apple orchards and fertile land made it a prized location.

Other islands carry names steeped in history and legend. Mama-Juda Island was named for an old indigenous woman who camped there every fishing season until her death. Bois Blanc Island, on the Canadian side, was a Huron village site in 1742 and later became a strategic location during conflicts between the British, Americans, and indigenous nations. Tecumseh and his warriors were stationed there in 1813 before the decisive battle that led to Perry’s victory in the War of 1812. In 1838, when rebels known as the “Patriots” occupied the island, they cut down its trees to gain a better line of fire for their cannons.

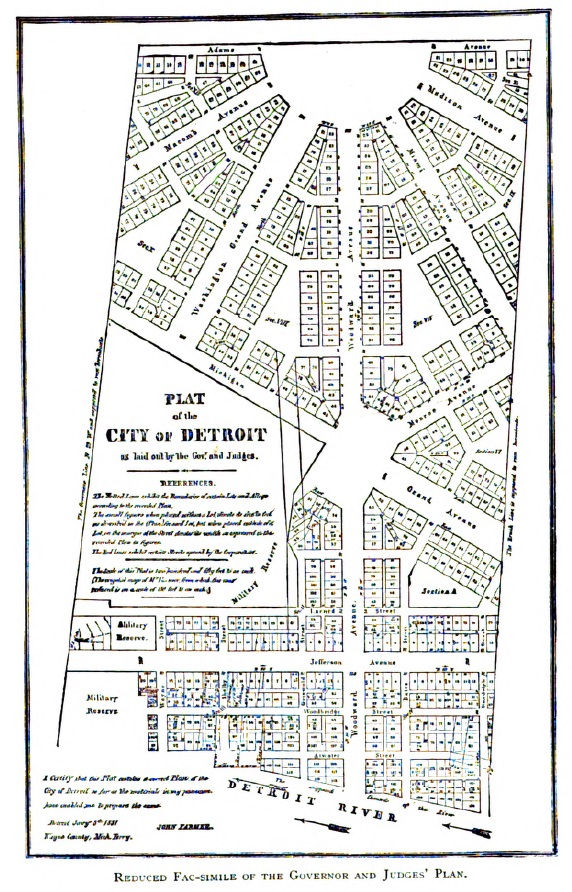

Detroit’s expansion along the river led to significant developments in wharves and docks. In the city’s early days, the river extended much further inland than it does today. At Woodward Avenue, it originally reached seventy-seven feet north of Atwater Street, and at Cass Street, it once covered part of what is now Jefferson Avenue. By 1796, maps showed two significant wharves: the Merchant’s Wharf and the King’s Wharf. As the city grew, the need for solid infrastructure became apparent, leading to the construction of permanent docks and landfill projects. Between 1826 and 1834, the riverfront was reshaped with material excavated from Fort Shelby, at a cost of over $10,000. These efforts transformed the shoreline into a bustling commercial district, with nearly five miles of docks lining the city’s waterfront today.

The river also fed numerous small tributary streams that once crisscrossed Detroit, each playing a role in the city’s early development. Savoyard Creek, a winding waterway, was used extensively for fishing and transportation. However, as the city expanded, it became an open sewer, leading officials to cover it with stone in 1836, converting it into an underground drainage system that still functions today. May’s Creek, originally known as Campau’s River, was another important watercourse, once home to some of the city’s first mills. Perhaps the most infamous of these waterways was Bloody Run, known in earlier times as Parent’s Creek. It earned its grisly name after the ambush and massacre of Captain Dalyell’s men by indigenous forces during Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763. Over time, these streams were either redirected, enclosed, or filled in, disappearing beneath the city’s streets.

The legacy of the Detroit River and its connected waterways continues to shape the city today. From its early days as a pristine, reflective expanse lined with canoes and windmills to its role as a modern industrial hub, the river has been both a witness and a participant in Detroit’s evolution. It remains a powerful symbol of the city’s resilience, a lifeline of trade and travel, and an enduring testament to the natural beauty that first drew settlers to its shores.

Comentarios