DET004 - Cadillac’s Land Grants: The Origins of Detroit’s Private Claims

- Patrick Foley

- Feb 11

- 4 min read

The founding of Detroit was not merely an act of exploration and settlement; it was also a complex legal and economic enterprise centered on land ownership. When Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac established Fort Pontchartrain in 1701, he sought not only to create a strategic military post but also to secure personal control over vast tracts of land. His initial grant, said to be fifteen arpents square, laid the groundwork for land distribution in early Detroit. However, historical records suggest Cadillac envisioned a far greater claim—one spanning the entire stretch of the Detroit River from Lake Erie to Lake Huron.

The French system of land grants in New France operated under a feudal-like structure, where large estates, known as seigneuries, were controlled by a seigneur who distributed smaller parcels to settlers. The king of France regulated land transactions through the Coutume de Paris, ensuring that even military officers like Cadillac, who established new outposts, had specific limitations on their property rights. Despite these restrictions, Cadillac made broad claims over the land surrounding Detroit, arguing that his efforts to establish peace with the Iroquois and prevent English expansion justified his request for territorial control.

Cadillac’s ambitions were met with official recognition. In a series of decrees issued between 1704 and 1706, he was granted authority to distribute land. He quickly took advantage of this power, issuing multiple concessions along the river. Among the earliest of these were two now famous grants: Private Claims No. 12 and No. 90, better known as the Guion and Witherell Farms. On March 10, 1707, Cadillac granted land to François Fafard de Lorme, a strip of four hundred feet in width and four thousand feet in length, amounting to nearly thirty-two acres. De Lorme was required to pay annual seigneurial dues and was obligated to grind his grain at the public mill, a condition that reinforced Cadillac’s control over local commerce. He was also forbidden from engaging in blacksmithing, brewing, or other trades without special permission.

Cadillac continued to grant land with similar terms to other settlers, including Jacob de Marsac Jouira, M. St. Aubin, and the widow Beausseron. These transactions reflected the early colonial economy, where landownership came with obligations, such as supplying timber for fortifications and contributing poultry, eggs, or grain on St. Martin’s Day. Another curious requirement was the planting of a Maypole before the seigneur’s door—an old European custom symbolizing fealty and seasonal renewal.

By 1708, an official survey reported that Detroit’s settlement had grown significantly, with 350 acres under cultivation. Cadillac personally controlled 157 acres, while French settlers cultivated 46 acres outside the fort’s stockade. At the time, 63 settlers lived within the fort, and 29 others had farms outside its walls. However, Cadillac’s tenure in Detroit was short-lived. In 1710, he was appointed Governor of Louisiana, and by 1711, he had left the settlement, placing his property under the care of Pierre Roy.

After Cadillac’s departure, the settlers, who had initially accepted the feudal conditions of land tenure, grew restless. By 1716, they petitioned the French king, complaining about the high dues and restrictions Cadillac had imposed. In response, the king revoked all of Cadillac’s land grants, ruling that they had been issued improperly and were excessively burdensome. However, the settlers were allowed to retain possession of their lands, ensuring that Detroit continued to develop.

Cadillac, now back in France, fought to reclaim his property. In 1719 or 1720, the king ordered that he be restored to the lands he had cleared and the rights over properties he had granted to others. However, the local authorities, led by Governor Vaudreuil and Intendant Begon, resisted this decision. They argued that Cadillac’s claims were impractical and that allowing him to reclaim his land would disrupt the settlement. By 1722, the king issued a new decree confirming Cadillac’s rights, but with limitations—he was granted control over lands he had directly cultivated but lost the ability to collect dues from traders.

The ambiguity surrounding Cadillac’s claims persisted even after his death in 1730. His eldest son later petitioned the French government, arguing that his father had been promised ownership of Detroit itself. However, no official records confirmed this claim. Instead, the issue became further complicated by a document known as the Maichens Deed, which surfaced in 1872. Purportedly executed in 1738, this deed transferred Cadillac’s holdings to a Bernard Maichens of Marseilles. Yet, the deed lacked specifics, and Cadillac’s heirs later argued that Maichens had never fully paid for the land, leaving the transaction unresolved.

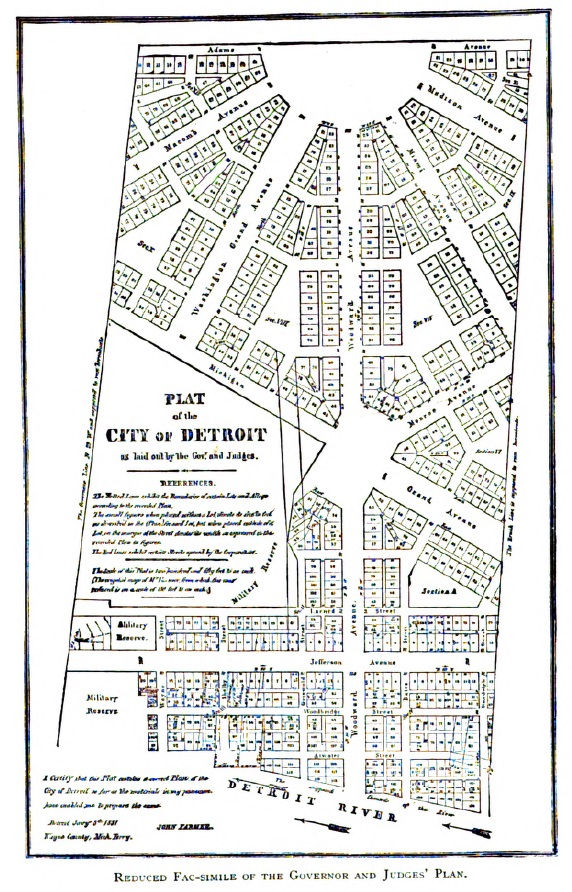

Throughout the 18th century, land distribution in Detroit became increasingly chaotic. Various French officials, including Tonty, La Forest, and Sabrevois, issued land grants despite lacking the authority to do so. The French government attempted to bring order to the process, requiring settlers to formally confirm their claims. In 1734, Governor Beauharnois and Intendant Hocquart initiated a new wave of official land grants, but even these were subject to confusion and disputes. The situation only worsened under British rule after 1763, when English officials attempted to regulate land ownership while simultaneously preventing settlers from acquiring land through direct deals with indigenous tribes.

By the time Detroit passed into American hands in 1796, the legal status of many land claims was uncertain. In 1804, Congress appointed commissioners to review French and British land grants, rejecting all but three as legally valid. However, in 1805, after a devastating fire destroyed Detroit, Congress expanded its review, ultimately confirming a broader range of claims. Over the next several decades, the legal wrangling over land continued, with additional claims being recognized, re-surveyed, and in some cases, challenged.

The legacy of Cadillac’s land grants is still evident in Detroit’s geography today. The city’s oldest private claims, many of which trace back to his original concessions, shaped the layout of early Detroit, with long, narrow farmsteads stretching back from the river. These early land divisions influenced later urban planning, leaving a mark on the city’s development that endures to this day.

Though Cadillac’s grand vision of personal control over Detroit ultimately failed, his actions laid the foundation for the city’s growth. His grants, disputes, and conflicts over land rights became part of the broader story of Detroit—a city built not only through industry but also through the complex and often contentious process of land ownership and governance.

Commenti